Planning a long hike

Photo by Geran de Klerk on Unsplash

I like this photo because it expresses that when you look into a thing, you enter a thing. And who knows where you'll end up? The woman in the photo is a bit like Alice, falling into Wonderland, perhaps.

Since the accident last July, what I've missed most is the simple joy of walking long distances. That's what I want again in my life the most, and I'm willing to become much more careful about alpine climbing in order to protect that. Essentially, I'm going to say goodbye to much "adventure" climbing. In the northern limestone alps around me here, bolts are going to be required. I've had two serious accidents -- they were both related to gear anchors. I have to conclude that I am simply not good enough with gear to be able to justify the risk. I'm likely a poor judge of anchors, and with the cost of failure so high, it's not the point in time to "fix the deficiency" by putting myself into school -- it's time to leave school with a failing grade.

So yeah, that's that.

And so, my mind turns to long hikes!

In 2017 when I walked the Swiss Via Alpina, I started out with my old Betamid tarp, a superlight sleeping bag, and a 3/4 length of foam pad. However, one night trying to sleep in that rig caused me to finally send the gear home. I wasn't willing to carry a heavier sleeping bag, so I had one inadequate to the trail -- I was cold! The next day I was tired. Now, for that trail, it's easy to sleep in a hotel or hut every night, so that's what I did going forward (and I had an amazing time). But I know I missed out on something special, too.

Going forward, I do want to experience the evenings and early mornings in the mountains. I notice that even when staying in a hut in the European Alps, the evening and transition to night are ignored. I'm usually taking a nap, then wandering down to the dining hall. Then I read a bit over a glass of wine and pad back upstairs to sleep some more. The night is generally avoided. And the morning is a time of people, chatter, lines for the bathroom, lines to pay the bill, things like that. In a way, you don't re-enter the mountains until you've been away from the hut for an hour or so.

The huts are also fantastic -- I'm just looking forward to another thing, that's all.

Therefore, I'm building my lightweight hiking kit and anticipating getting the metal removed from my foot so I can again enjoy long days of walking.

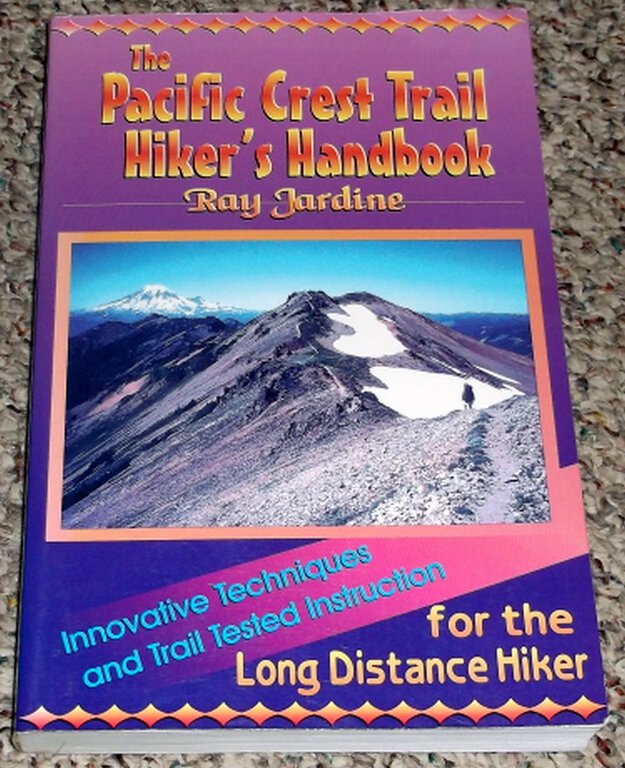

The Ray Way

Years ago I devoured Ray Jardine's excellent book on hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. It's out of print now, but really amazing. His ideas were helpful to me as a climber trying to shave weight off my shoulders and hips on mountain trips. Fast forward to 2021, and his ideas are fully mainstream now, and (hilariously) expensive to implement -- with all kinds of name-brands for packs and tarp-tents. Granted, the materials themselves, like Dyneema, are very expensive already. It's undeniably fun to geek out over this gear. Combine it with YouTube and hours of videos from hikers on long-distance routes testing out and vlogging about their experiences, you really never need to leave the house anymore, and can feel like a sturdy hiker anyway. So that's been fun.

For a long time I was a bivy-sack guy. I had the Advanced Research bivy sack with the tiny poles and mosquitoe netting. I remember once, bivied below Mt. Goode after a terrible brush bash up Bridge Creek, watching the infuriated mosquitoes insert their probiscuses through the netting in an attempt to reach my face 2 inches away. I would wake up in the night and see them patiently, penitently continue their work.

But a bivy sack in the rain is like rolling the dice. It might be fine, but it could also be that for some strange reason part of your sleeping bag is soaked. And considering a second or even third wet night quickly kills any remaining fun. It's just not adequate for many days out. Not for me, at least. I am a pussy, and am old enough now to admit it.

Tarps are very attractive -- I believe I can stay dry with a tarp. However, Washington and Oregon in bug season, just on the edge of snowmelt, is guaranteed to drive you insane if you can't escape from the bugs. I can hear them hatching in the yellow/pink algae-stained snow inches from my camp. If I'm going to stick to my plan to hike through a month of that, I've got to have an enclosed tent to escape from them.

Therefore, it's gotta be a tarp-tent! This is why I chose the Six Moon Designs Lunar Solo. Single-wall tarp-tent, uses one hiking pole and stakes.

I bought the tent from ChrisPacks.com (link to their page on Six Moon Designs. They are located in Fischbachau, just down the road from me. I was able to pick it up there, which was great.

Pack

The main problem with a single wall tent is ventilation. I'll bet the tent will be wet inside and outside every morning. I'll have a sponge or small towel to wipe down the inside, but I do hate stuffing a wet tent deep into a pack, then worrying about what that will mean later. Ray Jardine built his custom backpack to have a large mesh outer pocket exactly for storing a wet tarp. It would be easy to take it out at lunchtime and let it dry in the sun. It also means that your other gear won't get went if it's in an outer pocket. Therefore, my pack needs this feature.

Here in Europe, most backpacks look very sleek, and at most they'll offer an elastic band across the back to perhaps hold a jacket. But many American companies now offer the large mesh pocket. So it is to them that I turned, settling on the Gossamer Gear Kumo 36L.

36 Liters is a pretty special number for pack size. Most backpacks have a capacity like 48 or 50 liters. But in my experience, larger packs are too easily filled. I want a bit of struggle getting everything in. It forces me to go through an exercise questioning what I really need. Thanks to the roll-top opening, it can be overstuffed in a pinch, and there are special loops on the outside for attaching more things, even a bear container on the top. But in general, it is small, and that's a plus.

Lots of ultralight folks travel without the hip belt, but this isn't something I'm willing to do. I love hip belts! I don't like weight on my shoulders at all -- I much prefer to have a kind of 19th-century corset around my waist, and the shoulder straps floating free around my ears. This gives me an attractive "waspish" waist!

There are pockets on the hip belt, deep mesh pockets on the shoulder straps, and large pockets on the sides of the pack, too. This I really like for several reasons. For one thing, on a long through-hike, the food bag is heavy and large, and you want to carry it deep in the pack. During the day, I shouldn't have to open the pack at all, unless I need to get out a warm layer from the top of it. The food for the day can be distributed among these outer pockets, and the food bag and the all important sleeping bag will remain untouched until camp.

The Kumo comes with a "sit pad" which stiffens the back plane. For years I've used a Thermarest ultralight closed-cell foam pad as the backplane of almost every pack I've had, and I really like this "dual use" idea. My thought at the moment is that I'll allow myself the luxury of the sit pad depending on other factors. For example, I could leave it at home and stuff my pad into that space. However, if my pad is an expensive ultralight blow-up model, could there be abrasion rubbing against my back all day? Another idea is to put a Tyvek ground cloth for the tent in this space.

Anyway, I've never carried a sit pad, however, I did used to sit on my pack fairly often, something my trailmates avoided (wisely, I guess). This is an area in which I'm definitely going to overthink!

Groundcloth diversion

The whole sleeping setup is a complex system. An adjustment in one piece of gear forces modifications elsewhere until the system reaches a "fixpoint." It may seem odd that the tent groundcloth is in a relationship with the sleeping pad, but it very much is.

I'll talk about the sleeping pad more later, but essentially, I decided to go with an expensive fully inflatable pad. The danger here is around getting a leak. A leak can make the pad useless, and if you are sleeping on snow or in a storm, it can contribute in a real way to problems like hypothermia. Considering nearly week-long carries in high mountains, that's pretty bad. Therefore, the integrity of the pad needs to be protected in two dimensions: wear over a long period (months), and protection against sharp objects.

Long-period protection likely involves ground rules on what you do when. One idea here is to only use the pad at night -- only allow it to be inflated when safely inside the tent. Don't be that guy who inflates it at lunch for a nap on the sandy ground. I'm sure you'll get away with that a few times -- but 100 times?

Not likely!

As for sharp objects, they are more likely in some terrain than others. Deserts are spiky. Forests are softer, but man, pinecones can be brutal. Even alpine meadows can have spiky roots hiding in the heather. In general, I think the alpine world is simply too spiky to wave around a 200 euro ground pad without something extra.

Returning to the tent, my particular tent gets good reviews for durability. Many people go without a ground-cloth and appear to "win." However, long-distance hikers often report very tiny holes on the floors of their tents that don't have a particular acute cause (that they remember). So it does seem like constant deployment in harsh but not fatal (meaning, no puncture event occurred) is abrading something in a real way.

Since the tent is expensive and essential, I reluctantly conclude I've got to protect it. The question then becomes, Tyvek or Polycro? Tyvek is heavy, used in roofing to protect wood against getting wet, and incredibly durable. Polycro (or window insulation) is much lighter, but far less durable as well.

This fella made a great little video with a puncture test of Tyvek, Polycro and DCF (Cuben Fiber) material. Polycro and DCF broke if you sneezed at it. Tyvek was very strong.

My thought is that because of the importance of preserving the integrity of the overall sleep system, I simply must go with Tyvek. I'm going to cut mine down to the smallest reasonable footprint, and I'll report the weight here.

Sleeping Pad

It came down to a competition between the Thermarest NeoAir XLite (oh God, these names...!) and the Nemo Tensor Insulated. Both pads offer a "Regular/Wide" configuration, which is a regular full size (I'm 5'11"), but which provide extra width to prevent that great sadness of the night: cold arms. Don't laugh! It will wake you up, cause you to fold your arms and resolve to keep them locked together -- only to fail and again be awoken.

There is a new Thermarest pad, I forgot the name, but it's black, it is smaller and lighter -- and made of even thinner material. Cost reaches 250 euros, and this is just getting ridiculous, especially when you think how easily a leak can occur in these things.

The XLite is getting hard to get in Europe at the moment. The Nemo Tensor is a bit cheaper, and not tapered at all -- it's just a great big rectangle. I didn't like this at first, but then I considered how I sleep. I am all over the place. Sometimes on my stomach with an arm under my head. Sometimes on my back or side. I think, given that I want to do a long trail of weeks or months, I should prioritize sleep. That means to get a situation as close to a bed as possible.

I'm thinking about my psychology as well. In Europe, with uncomfortable sleep in a tent, I'm likely to retreat into huts or hotels, which I don't want to be forced into. In America, with no other choice, I'm likely to get sick or resentful and exit the hike -- or spend too much time recovering in towns.

I become very scared and selfish around sleep. Here's an example. The truth is that I snore pretty loudly. I really wish it weren't so, but it is. I even had an operation once to reduce it, but it didn't help (just hurt like hell). So if I sleep in a hut, I am probably disturbing someone. Some people sleep right through my snoring. Others...well, let's just say I can see it in their faces in the morning.

However, if I think I'll have to suffer a sleepless night, I get rather panicky. Push comes to shove, and I'll get my sleep, even if (I'm sorry to say this), I'm keeping you awake. So much for Buddhism!

Therefore...it's all to the good if someone like me has a camping setup that he enjoys, because he's more likely to feel that it's possible and even fun to sleep in places away from others.

(So yeah, I'm doing all this for you, clearly!)

Oh, the pad has an R-value of 3.5, which should be fine for warmth, though this is less than the NeoAir XLite's value of 4.2 (2.0 is pretty much the minimum if you may sleep on snow). Also, the fabric is 20D, versus the XLite's 30D -- therefore, it's again essential that I baby this pad -- and why I'm feeling even more sure that I've got to go with the Tyvek ground pad. I also bought the pad from ChrisPacks.com (they wrote a nice review of it (in German, volks!), as they liked it quite a bit. You can read that here).

Food

Food is important! I remember how delicious the freeze-dried meals were on our Picket Range trip in 2004. We only carried a little fuel, so the rule was that we boiled 1.5 pots of water each night, and that sufficed to rehydrate the meal packet for 3 people. Big days require big caloric input, and I'm not even sure how the body can make that work for months at a time. I'm told that we adapt! The longest I've walked unsupported is 7 days, once in 2003 and once in 2004, with lots of off-trail travel and technical climbing thrown in. I was a lot younger then, and there is still a great difference between 7 days and several months. So I've got to pay better attention to this stuff.

That said, I'm really excited about "cold soaking." As it turns out, I can bring food like noodles, cous-cous and other things on the trail without a stove. I can soak the food in water for a few hours in my pack, then eat it.

In fact, I tried it just now with a mug of cous-cous. Man, it was delicious! Okay, I added a lot of salt and pepper and even some olive oil. But it's just like it was cooked.

Cold-soaking saves weight, and it means that several camp chores can be eliminated. No need to boil water. Also, eating is done on the trail or "near" the trail, meaning, that with this strategy it even makes sense to have dinner on the trail then walk a bit further before placing your camp. This reduces food preparation anywhere near your sleeping area, which is good against critters (and even an essential idea in bear country).

What I find for myself is that fat is the key requirement for my satisfaction, and then spice comes in second. Beyond that it's a preference for anything high in calories, and I particularly love meat and cheese. Sweet things like chocolate are okay, but I'd prefer Wurst and Käse any day.

I like coffee, but I don't "need" it, thank goodness, because that's a lot of weight and complexity.

So I think the cold-saoking lifestyle (lol) will be a fit for me. Hot meals will be something to enjoy in town.

I'm looking forward to exploring this with shorter hikes in the Alps this summer. Another interesting issue here is that I'm looking forward to a kind of semi-retirement in the next few years. I realized I could do that when I discovered long-distance hiking and meditation. These two activities are so beloved, and they "don't cost anything." After you've picked yourself up off the floor from your laughing fit, you'll still have to admit they can be pursued more cheaply than many other activites, m'kay?

However, to make hiking cheap in the Alps, you do need to be able to eat without restaurants. So if I put in some focused thought to providing myself good, cheap, fatty cold-soaked (or cooked) meals, I can enjoy an evening without feeling deprived.

Essentially, I wouldn't be able to afford semi-retirement if hiking meant some variant of what I did on the Red and Green Via Alpinas -- restaurant food every night, and huts or hotels. I never added up the cost, but I'll bet it was really high! So for my own freedom, I've got to look deeper into food and sleep systems, and make choices that are different from what I did before.

Before, it was all about convenience (in and out before the weather window closes), luxury (for good sleep), and rich, fatty restaurant food (carbo-loading for a climb).

Tiny grains of sand

We really have to watch out for feeling deprived. If you let that build up, there is anger and resentment behind it. Ultimately you'll be angry at people you see enjoying restaurant food, or sleeping on comfy mattresses when you don't. And that anger will kill the joy of the whole trip. Who wants that?

And it's ridiculous anyway! Nobody forced you out here -- all of this is your choice. So you enter into a war against yourself. Just dumb.

So, following the Buddhist "Middle Way," we shouldn't suffer too much, nor should we make it too easy on ourselves. It's absolutely vital that we take seriously those "frivolous" comforts that we're ready to blithely eschew at the beginning of our Great Adventure.

Don't abandon them! Instead, make a special place for them in your hike. Yes, trim them down in various ways. But what remains is vital.

Flow

In order to experience timelessness, we need to minimize sharp transitions in experience. On the meditation cushion, I'll sometimes feel a severe itch on my neck or face or arm. I have to make a decision: should I scratch the itch? Because flow state is interupted for short-term gain. The mind is a trickster. When confronted with my will to hold a line, it will go a bit crazy, coming up with many reasons one after the other why I should scratch or adjust in some way. The only correct response is to harden against it -- in fact, to use it's capriciousness as a kind of homeopathic medicine to strengthen your will (or you could think of a vaccine, which includes some amount of the pathogen).

The question of consciousness is not really settled. It's certainly a good approximation to imagine the mind is in the human head, and that it cannot affect things outside, even though, thanks to psychology we're beginning to admit that our view on those outside events can vary radically based on our beliefs, assumptions and current emotional state. However, it's also a useful assumption to imagine that when you make up your mind, the world itself will test your resolve.

This is the same everywhere, and why should hiking be any different. So, visits to towns are, in my current view, an interruption to flow state. Successfully long-journey walkers attest to this. They note that time runs like water in towns. And that one day leads "logically" to another day spent there. Tasks accumulate, and in time, the flow state of the trail is just a memory.

At this point, you need to use your will -- you need to be stubborn. And once you do, the "world" will test you. Equipment will break. Easiest solution? Make your way to a big city with all the modern gear?

Don't do it.

Much better to do without.

Anyway, there is much more to say. I didn't mention my quilt yet! I really do enjoy delving into this subject, and bringing all my pet concerns with me. They peek out at me from behind new or unusual subjects, like whistling marmots. Looking into water filtration systems, I think about the sometimes uncomfortable position we occupy between embrace of the world and the need to shield ourselves against it. Too much shielding will harm us. Therefore, I've decided that yes, I will use a water filter, but in high country with snowfields and glaciers, I'll drink right from the streams, honoring the old rule about dipping our cups that Theron and I formulated on the Ptarmigan Traverse.